🛠️ From moving objets to move knowledge.

How our relationship with work has changed

A hundred years ago, the concept of work was much simpler. It was something you could see, touch, and measure. Work primarily involved physical effort, being present in a specific place, and performing tasks that often resulted in a tangible product: assembling parts, constructing buildings, or farming the land.

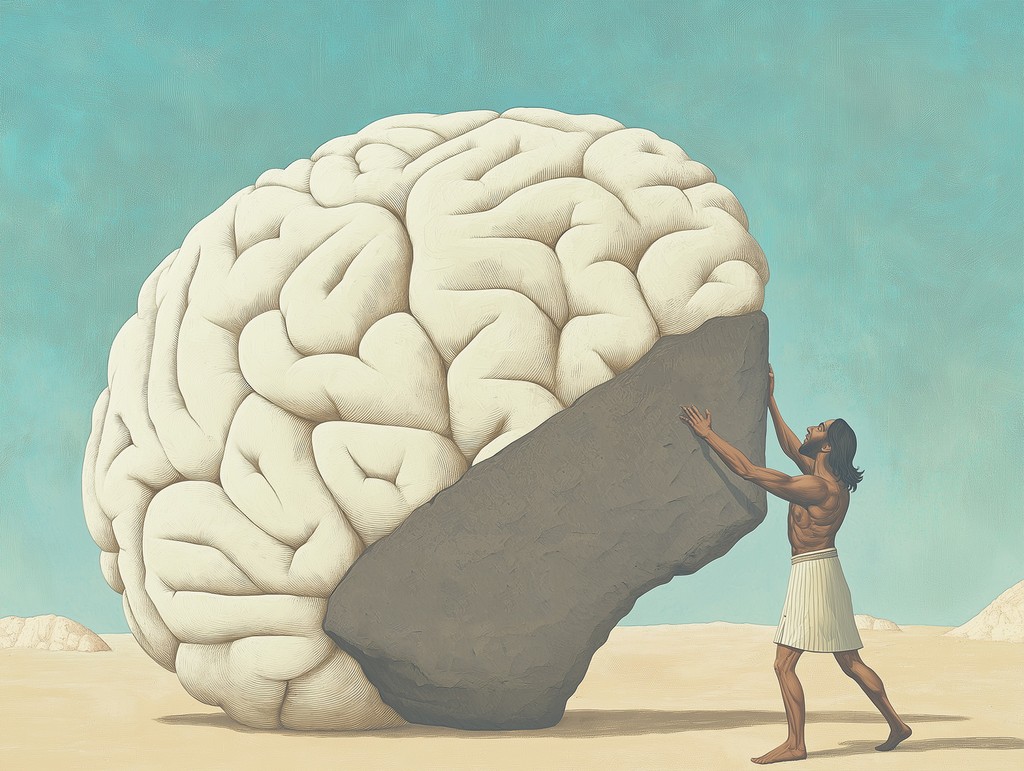

In short, work was directly tied to moving things from one place to another—materials, tools, or finished goods. But is this definition of work still relevant today?

The short answer is no, or at least not exclusively. Drawing inspiration from Bertrand Russell’s theory on work, we can understand how this transformation has occurred on two main levels: physical work and intellectual work. Russell defined physical work as directly modifying the state of objects, while intellectual work moves ideas, develops them, and disseminates them. Both are essential for civilization, but the balance between them has shifted dramatically.

Over the years, I’ve witnessed how this change in the definition of work impacts organizations, teams, and, most importantly, individuals. We’re living in a historic moment: work has been redefined as the management of knowledge, completely transforming how we collaborate and create added value.

From physical work to knowledge work

A century ago, most jobs required physical presence and a direct relationship with tools or materials. Production processes were mechanical and visible—in factories, fields, and mines. The success of an economy was measured in units of production, tons of steel, or barrels of oil.

Today, the global economy relies heavily on intangible industries: technology, information, creative services, and consulting. What we move from one place to another is no longer materials, but ideas and knowledge.

The "product" of our work is often intangible. A software application, a brand strategy, or a user interface design—these are all outcomes of knowledge work, a concept that Russell had already anticipated in his time.

The Impact of digitalization and globalization

Digitalization has been the key catalyst for this transformation. Digital tools like Figma allow us to collaborate in real time with people anywhere in the world, eliminating the need for teams to work in the same physical space.

For example, in my experience leading design teams across continents, I’ve seen how asynchronous communication and collaborative platforms have enabled a team in Europe to develop prototypes while another team in the Americas evaluates and optimizes them.

Globalization has also expanded the scope of intellectual work.

Today, the challenges we address as knowledge professionals have global implications: improving the user experience of an app used by millions, designing products that are inclusive across cultures and contexts, or ensuring our technological solutions respect user privacy. These are complex problems that require far more than moving objects—they require moving ideas, questioning assumptions, and connecting diverse perspectives.

The ongoing relevance of physical work

However, this doesn’t mean physical work has disappeared. Quite the opposite. Supply chains, construction, agriculture, and manufacturing remain essential to the global economy. What has changed is the perception of work as a whole. In many cases, physical tasks have been replaced by automated technologies, and in others, they are in the process of being automated.

A clear example is factory automation, where robots perform tasks that once required human effort. Yet there are areas where human intervention remains irreplaceable: tasks requiring delicacy, adaptability, and creativity—qualities that machines cannot yet replicate. While knowledge work has taken center stage, physical work remains the foundation that sustains our societies.

Looking ahead

In the coming years, we’re likely to see the boundaries between physical and intellectual work blur even further. Technologies such as artificial intelligence, advanced robotics, and augmented reality are transforming the way we work, enabling people to combine manual and cognitive skills in ways previously unimaginable.

As a UX designer, my role is to be at the center of these changes. We design not just to solve current problems but to anticipate the needs of a rapidly evolving world.

User experience is no longer just about how we interact with an app or a device; it’s about creating ecosystems that empower people to work more efficiently, inclusively, and meaningfully.

In summary

Work, as Bertrand Russell defined it, remains the foundation of our civilization. What has changed is how we perform it, the problems we solve, and the impact we create. We’ve shifted from moving objects to moving ideas, from working together in physical spaces to collaborating in digital ecosystems, and from mass production to human-centered innovation.

The challenge now is to ensure that this shift benefits everyone. We must find ways to close gaps, balance the physical with the intellectual, and design a future where work is not only a means of subsistence but also a source of meaning and human connection.

.see also